The origins of the Great North Road by David Smith

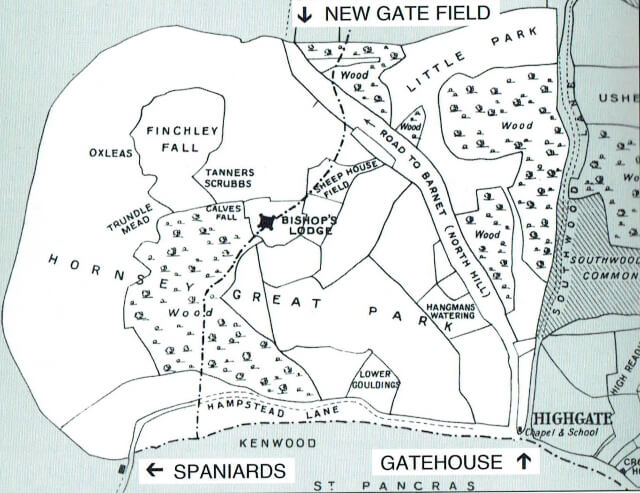

Up until the 14th century, much of Finchley was dense woodland, known as Finchley Common, and East Finchley, then known as East End, was little more than a scattering of settlements on its south-eastern edge, bordering the Bishop of London’s hunting park. The existing main route out of London avoided the wooded common, following a somewhat boggy path along what is now Colney Hatch Lane.

In around 1300 the Bishop of London created a new route for the main road heading north out of London to the north of England, which became known as the Great North Road. The route began at Smithfield and passed through Islington, Highbury and Holloway, along the route of the current A1, and then up Highgate Hill, North Hill and became today’s Great North Road through East Finchley.

A road to nowhere

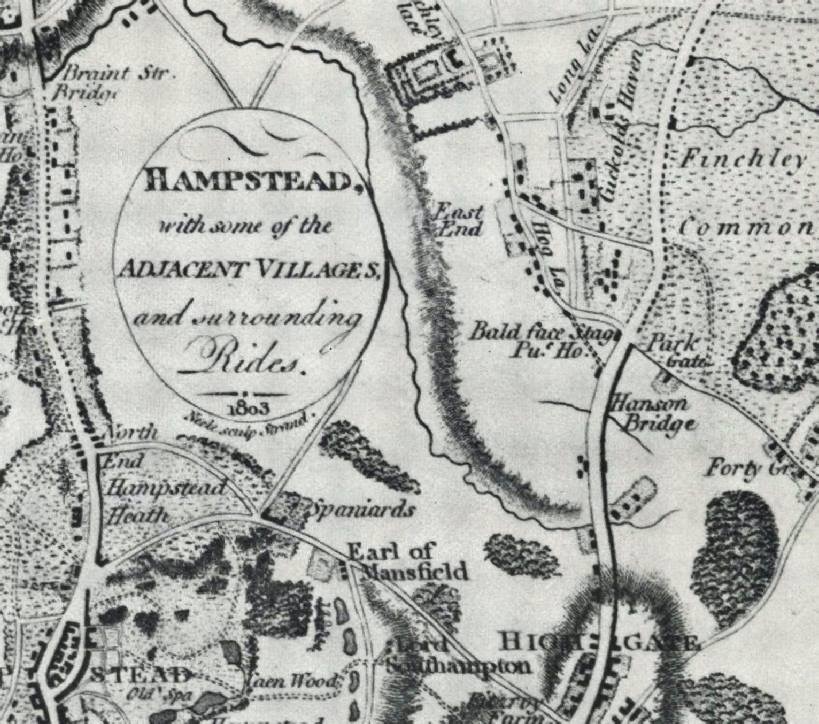

By 1444 maps show a bridge, later known as Hanson Bridge, crossing the Mutton Brook – a tributary of the River Brent, which rises in Cherry Tree Wood.

The road initially followed the line of Market Place and The Walks to King Street, which was the boundary of the Bishop’s land. Beyond this point the road simply opened out onto Finchley common.

Eventually the road was extended across Finchley Common via Browns Well (near Strawberry Vale), and continued north to join an existing route out of London (via Colney Hatch) at Whetstone.

Distances to the north were measured from Hicks’ Hall, the former Middlesex magistrates’ courthouse, which was located at the southern end of St John St, Smithfield, and were marked by a large stone – a milestone – every mile. The first milestone was at Islington Green, the second at Highbury Corner, the third at Holloway, the fourth at the foot of Highgate Hill, the fifth on North Hill and the sixth stone where East Finchley High Road meets the end of Bedford Road. Of these marker stones, only the Five Mile Stone on North Hill still remains.

Highwaymen and hangings

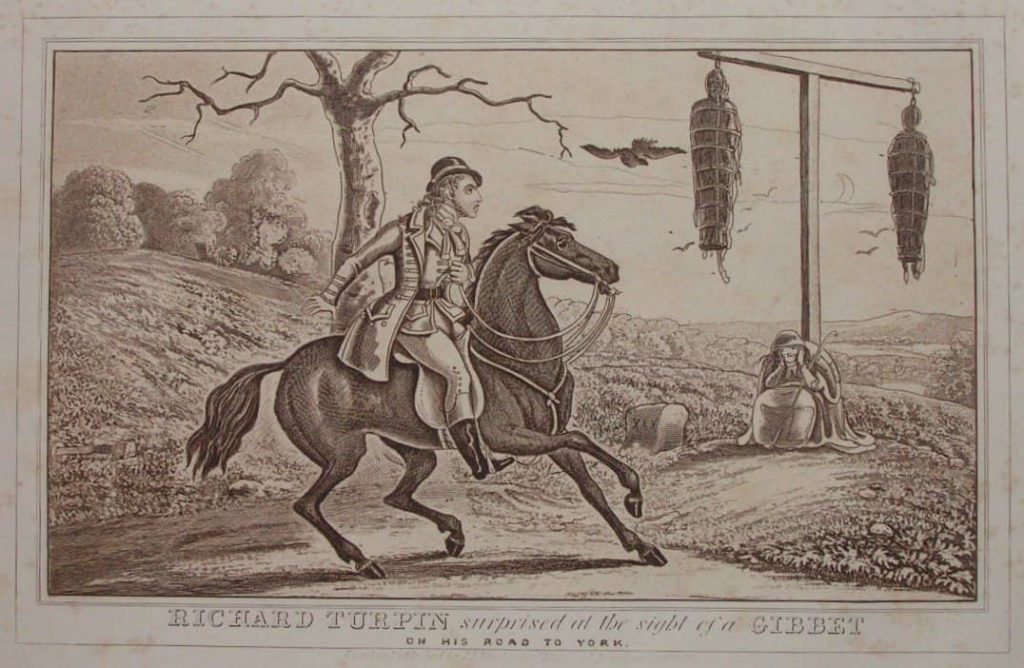

In the 1700s, Finchley Common was one of the most dangerous places in London on account of the highwaymen. The mounted robbers usually patrolled the main roads out of London where there was heathland or woods to hide in – and Finchley common was one of their favourite spots. Famous villains associated with the common include Dick Turpin and Jack Sheppard.

Oak Lane is in fact named after Turpin’s Oak, an ancient oak tree which stood at Browns Well on Finchley Common, where Dick Turpin was said to linger. When the tree was finally cut down in the 1950s it was found to be full of old musket balls, which were fired at the tree by travellers, just in case it concealed a highwayman. It must be noted that none of Turpin’s robberies actually took place on the Great North Road, however his spirit is said to haunt The Spaniard’s Inn, where his father was the landlord. Turpin kept Black Bess at the nearby tollkeepers cottage and there is still a horse trough there to this day.

Another notorious highwayman, Jack Sheppard, made his escape from Newgate Prison in September 1724 reputedly disguised as a butcher wearing a blue and white striped apron. He made off up The Great North Road but was recaptured in East Finchley and held overnight in the George Inn in The Hog Market until the police arrived to arrest him and return him to prison.

Left hanging

Such was the problem of highwaymen that a gibbet was erected at the Six Mile Stone in East Finchley. Here highwaymen were executed and their bodies left hanging from chains to deter others.

An excerpt from Julian Woodford’s ‘Stick Up at Six Mile Stone’ published in Spitalfields Life:

“Shortly after 5pm on Thursday 11th March 1773, Henry Cothery was driving his wife and four-year-old daughter Ann in a small one-horse chaise across the common towards their home in the City of London, having spent the day visiting his elderly father in Barnet. As they neared Six Mile Stone, they were clumsily overtaken by a man on horseback. Cothery was remarking that the man must be drunk when he turned, whipped out a pistol and yelled ‘Stop, your money!’

Cothery’s attempts to fob off the highwayman with a couple of coins backfired when the fellow grew more aggressive. Little Ann Cothery became tearful and the man softened, saying ‘Don’t be frightened, Ma’am,’ but persisted in his demand. The Cotherys had only a few pounds. Fearing for their lives, they handed over the money and the robber galloped away towards London, as Cothery yelled ‘A Highwayman, A Highwayman!’

Some passersby on horseback gave chase. As the pursuit careered down Highgate Hill and into Holloway, the posse grew larger and a mad chase ensued, with the highwayman flying through turnpike gates and occasionally turning to fire his pistol. Eventually, his horse tiring, he was cornered in a brickfield to the north of Shoreditch and forced to surrender. Identifying himself as Thomas Broadhead, he was dragged to the magistrates’ office in Worship St and confronted by Justice Davy Wilmot, the much-feared and satirised magistrate of Bethnal Green.

Wilmot was an illiterate builder and slum landlord who had risen to the dizzy heights of the magistracy through a corrupt trade in verdicts, pardons and bribes. Broadhead was charged with committing multiple highway robberies that afternoon and, when he was tried a few weeks later at the Old Bailey, Henry Cothery and his wife were witnesses. The evidence was conclusive and, despite six character witnesses in his favour, Thomas Broadhead was found guilty and sentenced to death. He was executed in Newgate and we may presume his body was carted back to East Finchley and exhibited upon the gibbet at Six Mile Stone.”

© Spitalfields Life

Further reading: Stick up at Six mile Stone by Julian Woodford

By 1712 the road had become so busy that a toll was introduced to pay for its upkeep. The road through East Finchley was also rerouted to follow the route of the current A1000 High Road. The section from Hanson Bridge to the north was named New Gate Lane and followed a straight line to what is now the crossroads at Fortis Green/East End Road, passing through a toll gate close to where the station now stands.

A dirty business

Unsurprisingly, not everyone was willing to pay the toll. The nightsoilmen who brought their carts carrying “night soil” from central London, came as far as The Dirthouse (now The Old White Lion) public house, just south of the toll. The night soil and horse manure, which was to be used as fertiliser for the hay meadows, was dumped in the large field known as Dirt House Field between the Dirt House and the Jolly Blacksmiths (now the Bald Faced Stag) public houses. This also appears to be the origin of the name Dirthouse Wood, the name by which Cherry Tree Wood, directly across the road, was then known. Tolls were abolished in 1876, though the toll gate remained in place until 1901.

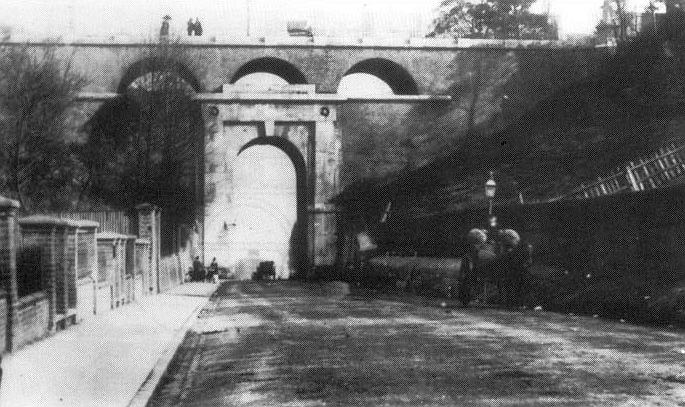

By the early 19th century the steep Highgate Hill was proving unsuitable for increasingly heavy traffic, and a new road, to cut into the hill at a shallower gradient, was proposed by a mining engineer, Robert Vazie. The brick built tunnel, carrying Hornsey Road over what was now a cutting, collapsed during construction in 1812, and a new bridge, constructed by John Nash was built using a series of arches like a canal viaduct. The road below was named Archway Road and opened in 1813.

In 1921 the Ministry of Transport designated much of The Great North Road as the A1 under the Great Britain Road Numbering Scheme. Archway Road was subsequently widened and by-passes were built to cut out the now congested centres of East Finchley, Finchley, Whetstone and Barnet. The stretch of Great North Road between East Finchley and Barnet was numbered the A1000, as it remains today.

© 2023 David A Smith

Acknowledgements:

History – 1500 to 1900 – Great North Road

Spitalfields Life

Finchley: Introduction | British History Online (british-history.ac.uk)

A1 in London – Wikipedia